Which way is the best, and how, to go wild camping?

Avoid costly kit beginner mistakes on your first wild camping adventure with this Ultimate Wild Camping Guide and Tips.

Whether it’s the increasing popularity of survival TV like I’m a Celebrity Get Me Out of Here, Survivor, Naked and Afraid, Oscar-winning movies like Nomadland (2020), or Log Hoppers – The official UK Nomads on YouTube, it seems the call of the wild has never been so popular!

However, my interest in wild camping followed a somewhat circuitous route. I was fascinated by Rupert Sheldrake’s Science and Spirituality, in which he advocated pilgrimages.

“Pilgrimage seems to be a deeply ingrained part of human nature, with its roots in the seasonal migrations of hunter-gatherers and, more remotely, in many millions of years of animal migrations.”[1] – Rupert Sheldrake

After visiting so many holy sites in India, he realised he hadn’t visited the holy sites in his own country, and founded the British Pilgrimage Trust.

When you mention Pilgrimage, most people will probably think of famous pilgrimages like the Camino de Santiago, to the shrine of Saint James the Apostle, the Hajj, to Mecca, or the Bodh Gaya, following the steps of the Buddha.

But a pilgrimage doesn’t have to be to a traditional religious site, the British Pilgrimage Trust recognises pilgrimages from “cathedrals and ancient trees to river sources, holy wells and standing stones” for the purpose of healing our “mind, body and soul.” And I saw literally hundreds of possibilities for a pilgrimage in the UK, which was very exciting, particularly a few on our doorstep.

I was also a big fan of Bill Bryson’s “A Walk in the Woods”, now a famous movie starring Robert Redford and Nick Nolte (more like me!) see photo below, and Henry David Thoreau’s, “Walden”, so I already had an interest in hiking and nature.

There was one small problem with beginning any pilgrimage, I didn’t have enough money to stay in Bed and Breakfasts, never mind hotels, along the way. So, following Bill Bryson’s example, I thought, why not wild camp?

In theory, I suppose you could plan your route between official campsites, but that feels less in the spirit of the ancient pilgrimage, or genuine-seeker-along-the-path sleeping by the side of the road, in my romantic imagination.

Not that you’re actually allowed to sleep by the side of the road in England, you need to be at least 100m away, but we’ll come to that later. And not that you’re actually allowed to wild camp without permission, either, and we’ll similarly come to that later!

The point is I was inspired to wild camp by these influences, take the law into my own hands come what may, and heal my mind, body and soul, whether I needed to or not!

The only other ‘small’ problem was I am in my fifties and I hadn’t got a clue where to start, a bit like Nick Nolte’s character, to go wild camping. I must emphasise wild camping because this post has little to no relevance to tourist-holiday-campsites camping, but rather the call of the wild, like Jack London! I wanted to engage with the Great Outdoors which fired my wildest imagination.

If you are similarly taken and inspired to go wild camping, you may find this deep-dive into my preparation for the journey–not the journey itself, which will hopefully be a video—useful and valuable in saving you time and money on your way.

Otherwise, good luck trying to save money on camping gear, ‘budget camping gear’ is almost an oxymoron! The more you try to save, the more you end up paying.

And if you’re an experienced wild camper, you will probably find my misadventures in planning and buying wild camping gear hysterical for all the wrong reasons! (I have sent more stuff back than I have kept!)

Either way, I hope you enjoy this post, and if you don’t want to miss other investigative-personal posts, please subscribe for free by clicking on the button below.

Words: 10,216

Reading Time: 42:56

Key Findings

1) You have a right to camp in Scotland (Land Reform Act (Scotland) 2003) and permission, rather than a right, in England in parts of Dartmoor National Park (National Parks & Access to the Countryside Act 1949)

2) Wild Camping is not illegal in the rest of the UK (Amendment to Section 1(4) Vagrancy Act 1935) while you are travelling, like on a pilgrimage.

3) In the US, wild camping (dispersed camping) is legal on most BLM land and National Forests.

4) The 6 systems necessary for Wild Camping Gear are: Carrying system; Shelter system; Sleeping system; Cooking system; Toilet system and, Navigation system.

5) Don’t laugh: My biggest wild camping costly kit beginner mistakes were a 90L rucksack, a 4.5Kg tent, a 2.4kg torn army surplus second-hand sleeping bag and broken compression sack, a 710g portable folding shovel, and a 1.43Kg Mobile Car Camping Stove, for hiking!

CONTENTS

2. Where can you go wild camping legally in the UK?

3. Why do you have to ask permission to wild camp on public land?

4. How many people go wild camping in the UK?

5. When to go wild camping in the UK?

6. What gear do you need to go wild camping?

6.1 Carrying System – What rucksack is best for wild camping?

6.2 Shelter System – What tent is best for wild camping?

6.3 Sleeping System—What sleeping bag and sleeping mat are best for wild camping?

6.4 Cooking System – How to filter water and how to cook for wild camping?

6.5 Toilet System - How do you go to the toilet when wild camping?

6.5 Navigation System - where to go wild camping?

7. Conclusion

1. What is wild camping?

According to the Collins dictionary, “Wild camping is camping in remote places with no facilities, rather than on campsites.”[2]

What is lacking from this definition is the timing and legality. Wild Camping tends to be overnight, on the way to somewhere else being hiked to, rather than staying for a few days or more.

As for the legality, the Camping and Caravanning Club’s definition, as one might expect, leaves you in no doubt, “Wild camping means you’re camping without the express permission of the land owner.”[3]

This is where we enter the grey area surrounding the legality of wild camping in the UK, which for me is part of the romantic adventure, alongside no power points, showers or toilet cubicles, and not being within throwing distance of an RV or Caravan! (But each to their own!)

2. Where can you go wild camping legally?

In Scotland, as long as you carry all your kit in—camping in cars or RV’s is not allowed —you have a right, and it is perfectly legal, to wild camp, thanks to the Land Reform Act (Scotland) 2003, as long as you follow the Scottish Outdoor Access Code, for example, camping away from buildings and roads, leaving no trace, and not camping in enclosed fields containing crops or livestock, except for seasonal restrictions, see below, applying to Loch Lomond & The Trossachs National Park.

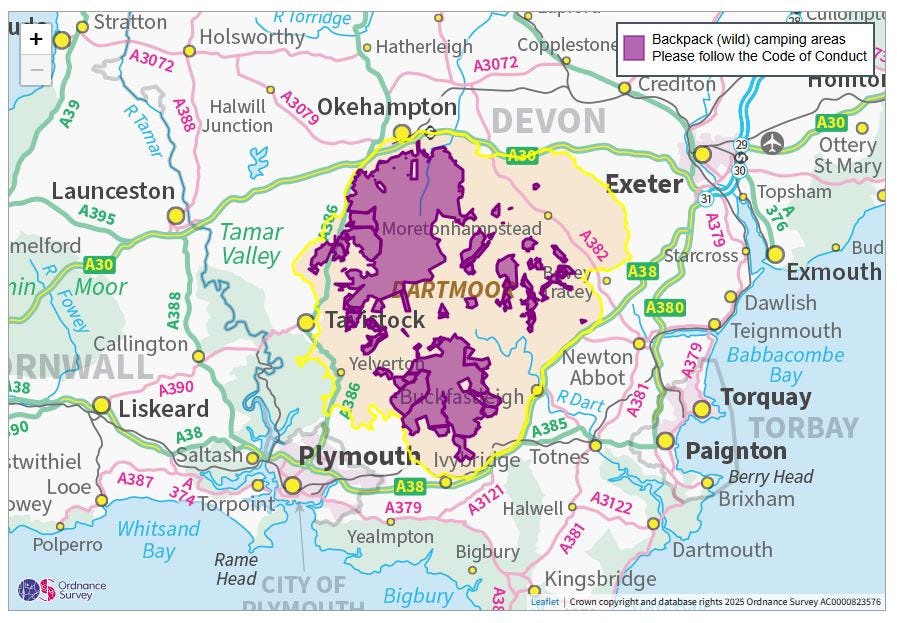

In England, there are limited parts of the Dartmoor National Park in the South of England where wild camping is permitted without permission— if you carry all your kit, no camping in vehicles, camp for one or two nights, and stay out of sight of roads or settlements— under the National Parks & Access to the Countryside Act 1949[4].

You can access an interactive map to see exactly where here[5]:

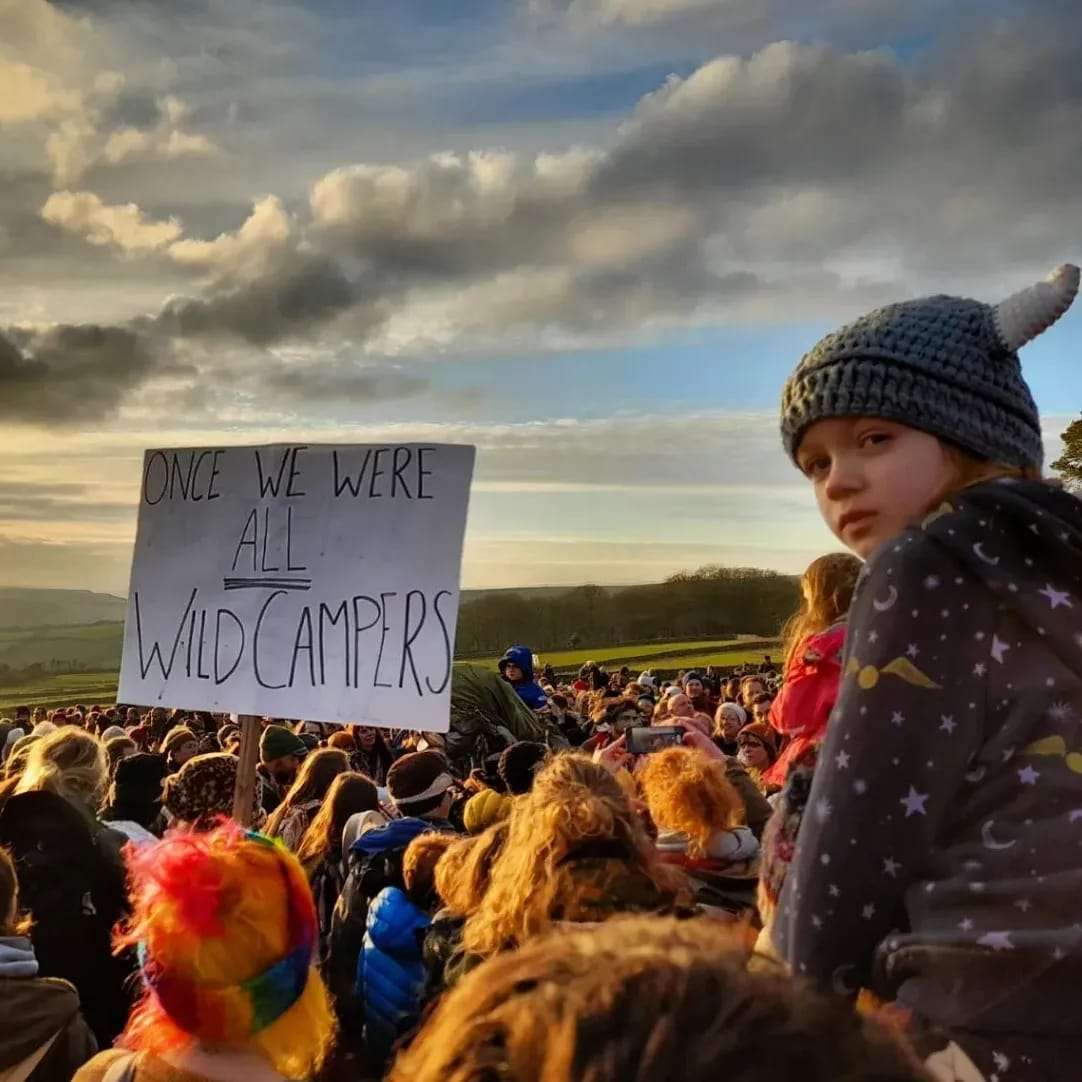

Although these parts may be reduced thanks to a recent legal challenge by Mr Alexander Darwall, a hedge fund manager who bought a 3,450 acre estate on Dartmoor in 2013—knowing there was an existing right to wild camp on the land—and initially won a court case to remove the right to wild camp on his land, without permission[6], but this was overturned by an appeal. However, in 2024 Darwall was granted permission to appeal this decision to the Supreme Court, which is currently pending. Mod is one popular YouTube influencer who is passionate against this threat to his right to wild camp on Dartmoor which he claims is more than a right, “it’s not [a] right you’re born with it, you know, it’s in our DNA, it’s that deep, it’s ingrained.” You can contribute to the legal fund to save the right to wild camp on Dartmoor here.

You can also usually camp for free in upland areas (above 400m) without permission—there are no mountain police(!)—including: upland areas of the Lake District, north-west England; upland areas of Wales; upland areas of north-east England, such as the North Pennines, the Cheviot Hills, the Border Moors and Forests, and the North York Moors.

“Stay out of sight and for only one night. A wild camp pitch must be above the highest fell wall (approximately 400m or 1200 feet high) and shouldn't be noticed by anybody else. This means staying away from any buildings or other wild campers. Don't camp next to streams or springs to avoid contaminating the water. Arrive late in the day (dusk) and move on at dawn..” – The National Trust

However, The National Trust don’t seem to understand the definition of ‘wild camping’ in spite of their guidance under, ‘If you do decide wild camping is for you…’, see quote above, because wild camping is by definition, camping without permission. So why are they giving you permission?!?

The National Trust seem to confirm their confusion by declaring a difference between wild camping and, what they call, ‘fly camping’ which they declare is illegal: “If your planned pitch is not above the highest fell wall this is illegal fly camping—not wild camping”[7]. This is nonsense. It is still wild camping, and not “illegal”.

They seem to be conflating wild camping with fly camping, whereas fly camping, like “fly tipping”, is leaving your rubbish, like litter or the remains/damage from a fire, which is against the Cardinal rule of wild camping: Leave no trace.

And genuine wild campers abhor fly campers, so it is a shame the National Trust seems to lump them together.

You can also camp in or outside a bothy in England and Wales without permission, such as Holme Wood Bothy in the Lake District, see photo below, and on the foreshore (below sea level when the tide is out) of a tidal river or beach[8]. Both 24-hour coastal fishing and navigation are rights under the Magna Carta. If you haven’t got a canoe handy, just carry a telescopic rod and reel (less than £10 online!) or a trowel to evidence your bait hunting!

If you buy a Waterway Wanderers fishing permit (less than £26), you are entitled to stay overnight on most Waterway Wanderers stretches for the purpose of night fishing.

Approximately 15% of the land in England and Wales is unregistered and, as the Land Registry post writes, “Much of the land owned by the Crown, the aristocracy, and the Church has not been registered, because it has never been sold”.

Since it is very difficult to determine who owns unregistered land to ask for permission, and if there is no fence, it isn’t necessarily trespassing to wild camp on unregistered land while travelling through, as long as you’re prepared to move on if requested.

Tara explains in Log Hoppers - The official UK 🇬🇧 Nomads, “if there’s no fence to cross, you’re not necessarily trespassing. We’ll check the register, we’ll make sure it’s not registered to anybody and if not, we’ll see it as fair game.” Tara and Mod’s YouTube channel is full of excellent advice about wild camping and fun, too, and I highly recommend subscribing. And Tara clarifies to avoid any confusion, “for the record, where possible, we tend to stick to recreational common land.”

You can find the registry land map here.

In the rest of the UK, wild camping isn’t illegal, with the proviso while you are travelling, but it isn’t a right like in Scotland, either.

“Wild camping is not illegal. It used to be, back in the 1930s. But…the Vagrancy Act 1935, Section 1(4), now reads: ‘The reference in the said enactment to a person lodging under a tent or in a cart or waggon shall not be deemed to include a person lodging under a tent or in a cart or waggon with or in which he travels.’ It’s an important change that effectively legalises ‘the traveller’.”[9]

Technically, wild camping is not a criminal offence, but rather the civil offence of trespass. You need to ask the landowner’s permission, even on public land, although wild camping is usually tolerated, if you follow the five Cardinal rules:

Camp 100m away from roads and out of sight of buildings

Pitch late (after sunset), strike early (before sunrise)

Don’t stay more than one night

Use a trowel to bury human waste at least 30m away from a water source

Leave no trace (No fires and no damage to the land)

But if you refuse to move when requested, or argue with the request, the Police can be called and you can be charged with aggravated trespass, which is a criminal offence and arrested.

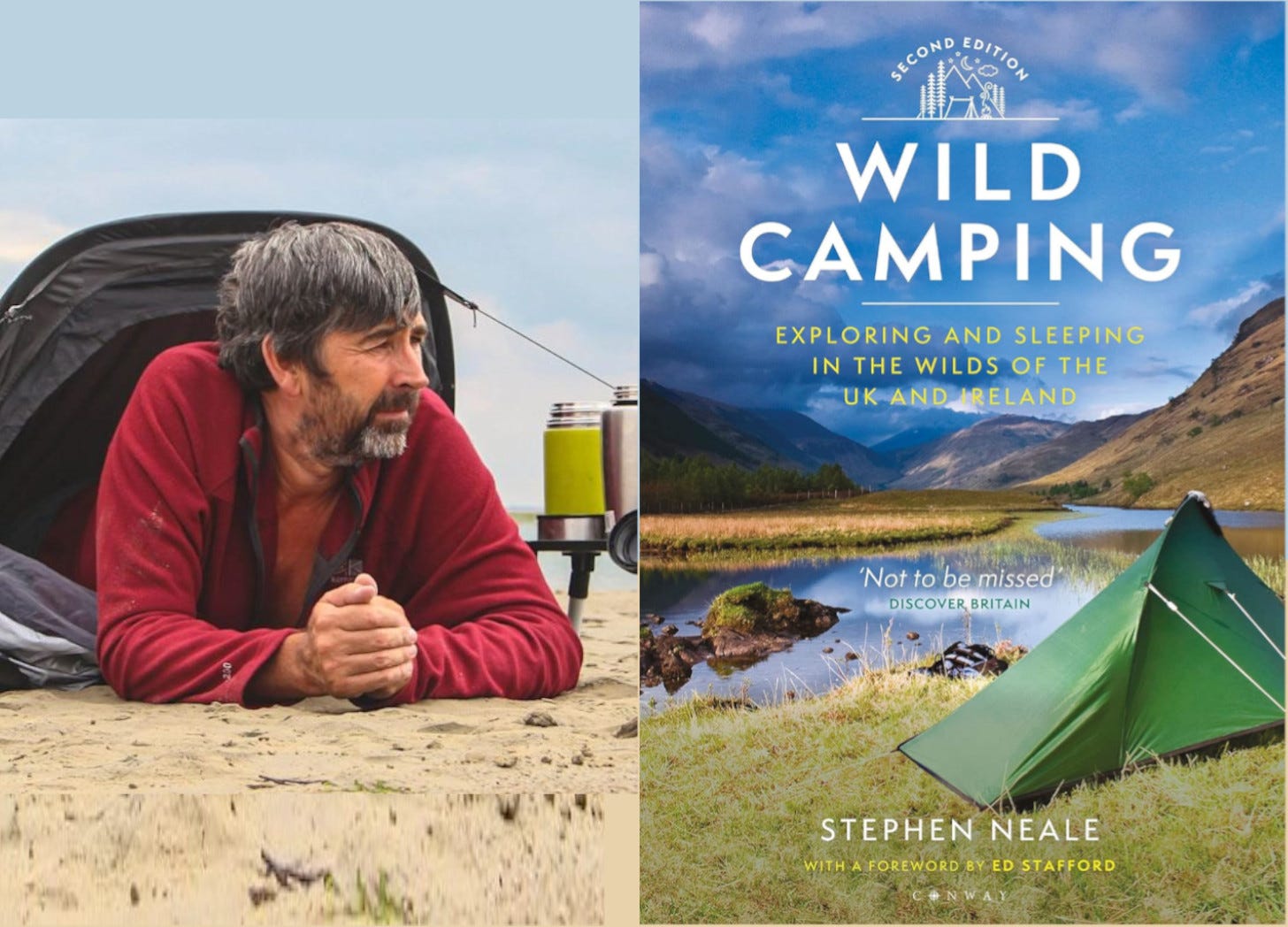

On Dialect Radio, Stephen Neale gives this useful advice if asked to move:

“If you do get woken up by a landowner say you’re on your way to the next town, you’re on a 2-3 day hike, if you explain that to the landowner, you’re not causing any trouble, you’re not a criminal, you have no intention of lighting a fire… I’ve got a bag here and actually look I’ve got a bag here and I’ve been picking litter up on the way there, they are almost always very very happy for you to be there as long as they understand why you’re there.”

Stephen Neale, see photo above, is my champion of wild camping in the UK, and author of the British ‘bible’ of wild camping, “Wild Camping: Exploring and sleeping in the wilds of the UK and Ireland” which I highly recommend, particularly for its lovingly described and detailed guides to areas to wild camp including grid references and communication links.

In the U.S., wild camping is known as ‘free camping’, ‘boondocking’ and ‘dispersed camping’[10], and more than 640 million acres, over a quarter of the US landmass, is public land managed by the federal government, most of which is open to dispersed camping. For example, wild camping is legal on most Bureau of Land Management (BLM) lands in 12 Western states, and most National Forests, although not National Parks, with a few exceptions, eg. Death Valley National Park.[11]

So how did we end up with such severe restrictions in England on public land? Surely, there must have been a time when Anglo-Saxons could roam freely and camp wherever they liked. And if there was a right before, who took it away and why?

You need to know this because I think you have a moral right to stop and sleep on your journey, particularly on public land, and especially on a pilgrimage to your British heritage.

“WHO – Every person

WHAT – has a natural-born right to sleep outdoors without paying…

WHERE – in the British Isles

WHEN – right now

WHY – because wild camping is too much fun to be wrong.”[12]

3. Why do you have to ask permission to wild camp on public land?

The Norman Conquest in the famous battle of Hastings in 1066 removed most of our rights, like the right to fish, the right to collect wood and the right to camp.

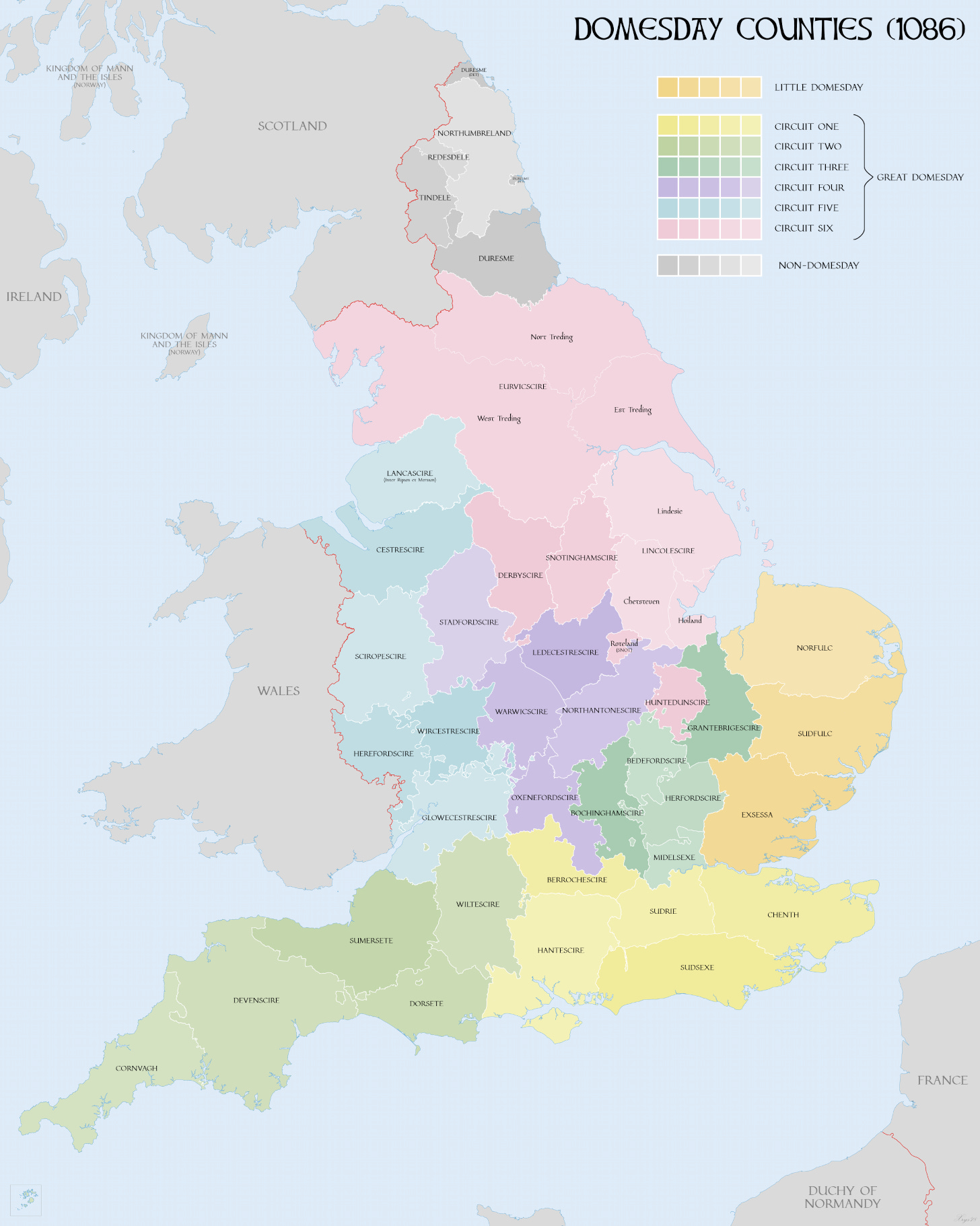

In 1086, William the Conqueror ordered the widest land registry record in history in the infamous The Domesday Book, to identify new landowners—because he had officially seized all the land and given it his cronies—to calculate what they might owe in tax and favour, see delineation of counties below.

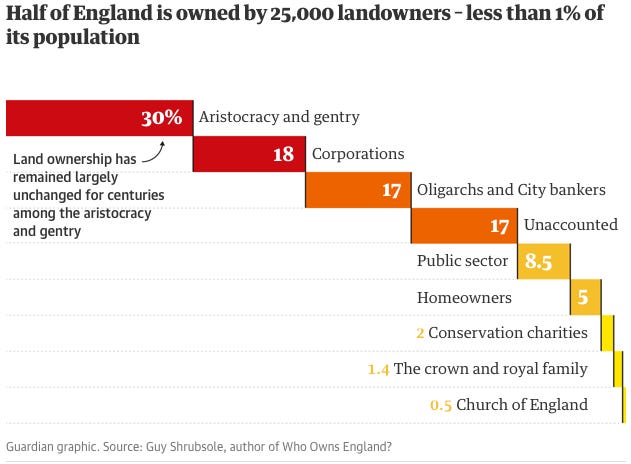

The Domesday Book removed the communal right of access over the land. Half of all the land in England is still owned by less than 1% of the population, approximately 25,000 landowners, and almost a third (30%) are the ‘Aristocracy and gentry’ —most of whom are descendants of 11th-Century Norman Aristocracy—see graphic below, according to Guy Shrubsole, author of ‘Who Owns England?’ (2019)

Further, Norman surnames like Baskerville, Darcy, Mandeville and Montgomery, still dominate at Oxbridge[13].

Therefore, unless you have the right surname you are unlikely to own land, in effect removing your rights to access the land to roam and eat, or make your traditional living, by hunting and gathering. All because your ancestors, unfortunately, weren’t a spivvy or mate of William the Conqueror, who stole the land, and him and his cronies wanted to protect their stolen land for their own leisure pursuits—not economic or living necessity— and keep the commoners out!

People were even executed under the new Forest Laws for camping, trespass, catching fish or deer to sustain their families, which is partly where the myth of Robin Hood living in the woods and stealing from the rich to give to the poor, comes from.

Until a couple of centuries later when peasant discontent and aristocratic landowner opposition to King John, combined to force him to draft the Magna Carta in 1215. This granted 24-hour access rights to the hills, mountain and foreshore, day and night, thus making wild camping a necessity, if not a right.

That’s why you could call the rights to wild camp you are left with in the 21st Century in England, a bad roll of the dice.

This is important to remember, like I said earlier, because I believe history asserts your moral right to access the land and sleep overnight, for the purpose of peaceably passing through, on your journey to a different destination, while following the five cardinal rules, above. We all have a right to sleep.

“EVERYBODY HAS a God-given right to sleep, whether they have cash in their pocket or not… Civil laws intended to protect the rights of landowners, tenants and other legitimate land users are not there to stop a person in transit from sleeping while causing no damage or harm. The knowledgeable wild camper is unlikely to break the spirit of the law.” – Stephen Neale

4. How many people go wild camping in the UK?

A UK-wide online survey commissioned by the Scottish government found that approximately 4% of respondents said they had wild camped (not in a campsite) in Scotland in the past 2 years.

If this survey used a representative sample of the population, and we assume a working population aged 18-64 of 40.46 million from ONS data, 4% would be 1.618 million. And these are only those who had wild camped in Scotland!

Still, that seems a bit high, but due to the nature of the activity it is hard to get data, and other estimates I’ve read of perhaps hundreds of thousands of wild campers, though not sourced, seem more realistic to me.

Either way, you are certainly not alone!

5. When to go wild camping in the UK?

The official camping season runs from March to September, which is important to remember if you plan on wild camping in Scotland because byelaws restrict camping during this period in approximately 4% of Loch Lomond & The Trossachs, and you will have to buy a permit. Needless to say, you must always follow local byelaws. Outside of this season, no restrictions apply there.

Otherwise, due to the ‘unofficial’ nature of wild camping, there is not really any official camping season you need to worry about, unlike Course Fishing, where you can be fined for fishing in the close season from 15 March to 15 June, even with a licence.

The only thing you need to worry about when it comes to four-season wild camping, is your gear.

6. What gear do you need to go wild camping?

Short of actually wild camping itself, choosing your wild camping gear is probably the most exciting thing about the hobby, and there are endless hours of recommendations on YouTube which can be overwhelming, and contradictory, for the beginner.

I have spent months buying all the wrong gear, sending it back, and buying new gear because I listened to the ‘experts’, not suspecting they might have an agenda themselves! I have no agenda because I have never been wild camping, and claim no expertise, except through what I have researched, and bought myself, but none of this equipment has been tested in the field yet, so please take these suggestions with a pinch of salt, and I will update this post when I have.

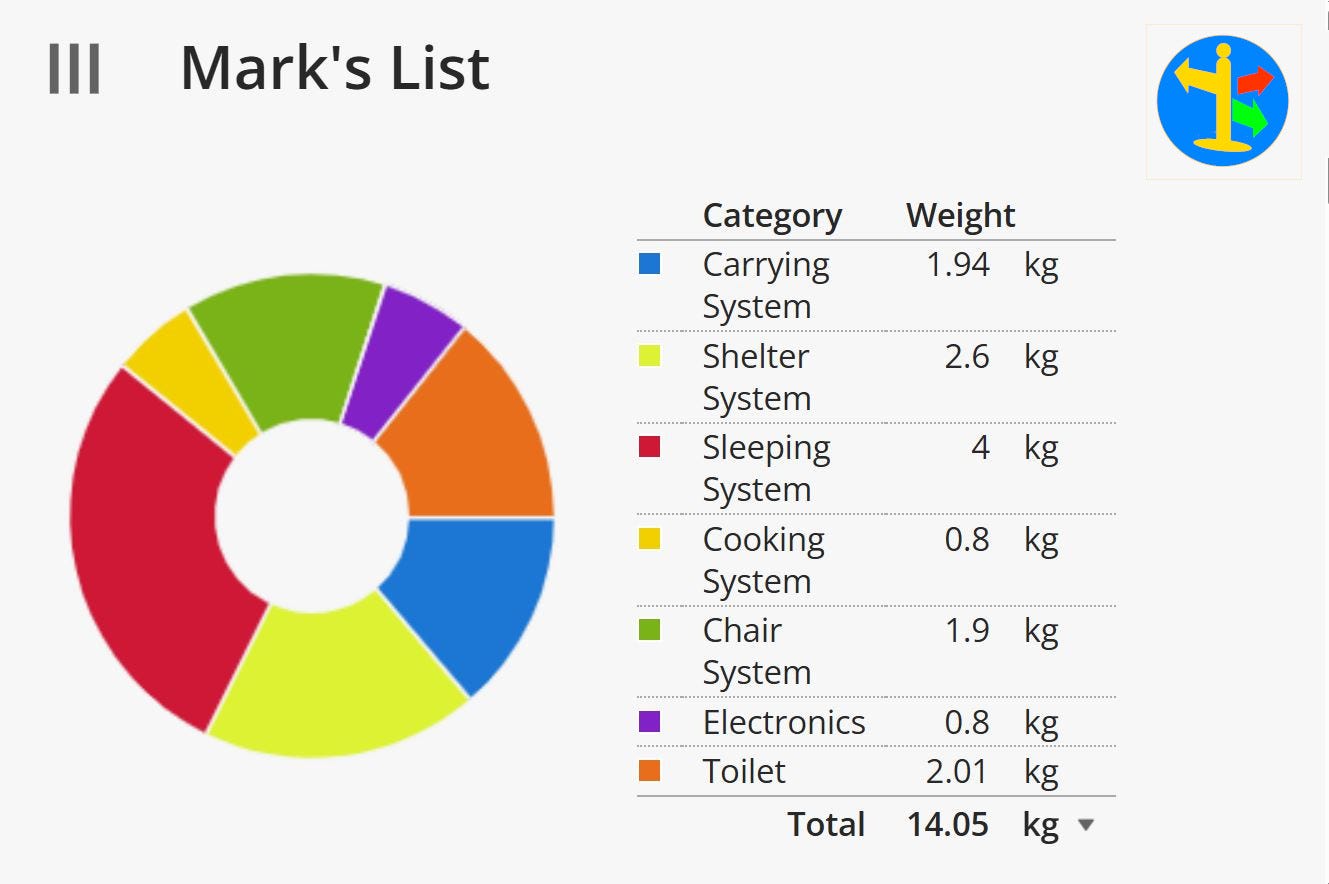

First, it helps to get your head around the idea of separate systems for each aspect that you will need for wild camping: Carrying system; Shelter system; Sleeping system; Cooking system; Navigation system.

These will depend on when you want to wild camp. While the more I learn about the benefits of Winter camping, such as no/fewer midges/flies/wasps/bees, fewer people passing and thus a lower chance of discovery, since I personally want to go three-season camping, I will focus on wild camping during Spring, Summer and Autumn.

6.1 Carrying system – What rucksack is best for wild camping?

Less is more. And it applies to rucksacks as much as writing!

I had thought that the bigger the rucksack the better, for the simple reason you can carry more, which I naively assumed was a good thing! So, I bought a 90L rucksack like Reese Witherspoon in Wild (2015) see photo above. Beginner mistake number one! You don’t want to carry more, particularly if you are hiking, you always want to carry the least practically possible, and then halve that if you can!

How do you know how much weight you should carry for wild camping?

You don’t start with the capacity of the rucksack; you start with the capacity of your body. Therefore, the starting point for any calculations is your own age, strength/fitness, height and weight.

I am in my fifties, 182cm tall, and at the moment weigh about 80kg (BMI 24.7) just inside the healthy range (although worryingly close to unhealthy—which is why I need to urgently hike!) and I am reasonably fit and strong for my age, albeit starting this new hobby rather late in life—but you are never too old to learn!

As a rough rule of thumb, you should carry between 15-20% of your body weight, which for me is, 12-16Kg, and scale this according to your level of fitness and the distance you intend to hike.

What volume of rucksack do you need per kilo of weight carried for wild camping?

There is no specific calculation or primary research that links, for example, a particular kilogram load to a particular litre capacity, because it obviously depends on gear density, packing efficiency and the dimensions of items.

However, as a rough guide, I found from trial and error that I need a 50-65L litre bag to carry between 12-16kg, rather than the 90L rucksack I had! If your rucksack is that big, you are probably going to end up carrying more, and making your life more painful.

I found a budget rucksack, with a minimal frame, strong 600D polyester fabric, good carry straps and belt, and very light (1.38kg). It is the Eurohike Nepal 65L, see pic below, and it cost me less than £30 including delivery and has excellent reviews on Amazon, and on YouTube.

If money was no object, I would either choose an Osprey Atmos AG 65 (£219) because it is the most well-recognised brand and has an excellent review, although it weighs 2.18kg, which is more than the Nepal 65L, but has a better frame, strap and belt system which will make it feel lighter.

If I was a nomad, using the rucksack on a daily basis for years, I would choose a US military Blackhawk Titan Hydration Pack which is stronger than both with 1000D rip-stop nylon, and a molle system for attaching more pouches and gear, even though it weighs 3.3Kg, and has only a 40L capacity, because I trust this review by Mod, as mentioned earlier, aka “the Log Hoppers – The official UK Nomads”, and this review, too.

In addition to the main rucksack, I bought pouches for my phone (£7) and glasses (£10.99 ), like these in the links, which attach to the straps of my rucksack using molle clips, because I thought when I am carrying the rucksack it may be difficult to access my shirt/coat pockets under the belt and straps.

These are examples of exactly what you don’t need to worry about, and if I had my time again, I would have bought an OMM Trio Map pouch (£30) instead, see pic below, or a simple fanny pack to wear in front, and keep my glasses and mobile there. The OMM pouch is particularly useful for hiking because it can protect your paper map and opens in a prone position, from your chest, to read it without removing the pouch (see Navigation System below.)

But I think my pouches still look cool, and they are handy! It’s not so easy to figure out how to attach them to the rucksack so I’ll show you the Molle clip I used, see pic below.

You can find a set of 52 useful molle/webbing clips here (£12.99)

The only other thing I would change about my carrying system if I could live my life again, is perhaps the colour of my rucksack, which I bought in bright red before I realised that stealth might just be a useful tactic in this particular hobby! (If you are an experienced wild camper, I told you, you would laugh!) But you must admit, it’s a lovely shade of red, and it will go well with my bright yellow puffer jacket—I’ll stand out like a traffic light!

However, on a more serious note, the best way to be stealthy is sometimes to look the most like everyone else and therefore, the least stealthy!

6.2 Shelter system – What tent is best for wild camping?

The three most important criteria when choosing a tent are weight, packed size and weather resistance.

6.2.1 Weight

As a general rule, the more money you spend, the lighter the tent will be. If you can, aim for 2kg for a one-or-two-person tent, and 3kg for a three-person tent. You will usually be able to split the weight if you are camping with a friend, for example, one of you can take the fly sheet and poles or tent pegs, and the other the inner tent and footprint (tent’s ground mat). However, it is important to note that a two-person tent is usually fit for one, and a three-person tent, for two.

But what did I do? I bought a cheap three-man dome tent which weighed 4.5kg because I liked the fact that it was cream (not exactly camo!), had ‘windows’, you could almost stand up in it and it was only £45! This kind of tent is great for camping with a car but not at all for wild camping. You can’t even split the weight with others because it is a pop-up tent which means all the poles were already integrated in the package, and it had no vestibule.

The vestibule, that triangular area between the sleeping area of the inner tent and the door of the outer tent, is very important for storing boots and rucksack and even cooking, particularly in rainy/stormy weather, but remember to always keep the door open to avoid carbon monoxide poisoning and never use a stove for heating a tent.

Unfortunately, most dome tents, like mine, are unlikely to have a vestibule, which means you have to store your gear inside the sleeping area.

When the sleeping area for two people is 120cm x 180cm, like my dome tent, that gives you a width of 60cm each, and if you are both 5’11”, like me, it doesn’t leave much room for your rucksack or boots, except on top of your sleeping bag! Beginner mistake number two!

I sent my cream dome tent back and, after much research, selected the Naturehike Cloud-Up 3 Upgrade for under £120 on amazon., which had excellent reviews on Amazon, and on YouTube.

Notice how the light green colour blends in with the grass of the surroundings, a bit more than my former cream dome tent did—looking more like an observatory!

And the Naturehike Cloud-Up 3 Upgrade only weighs 2.6kg, practically half the weight of my first tent!

Now, if you remember, my rucksack above weighs 1.38Kg, plus this, 2.6kg, so we are already up to 3.98kg, or a third of my minimum target weight of 12kg, carrying only one item! It soon adds up.

Use lighterpack.com, a free online tool to keep track of the total weight of your camping gear, see my early packing list below, and try not to laugh too loud—particularly about the 2kg toilet!

6.2.2 Packed size

The packed size of my Naturehike Cloud-Up 3 Upgrade Tent is 45cm x 15cm, which I checked before purchase, can easily fit vertically in the main compartment of my Nepal 65L. However, my cream dome tent had a packed circular diameter of 78cm x 10cm, and there was no way it was ever going to fit on any rucksack ever invented! It is a fat lot of good for hiking—never mind a pilgrimage!

So, please do, check the packed size of your tent, because ideally, for wild camping, you want to keep everything inside your rucksack so you are not advertising your intentions to camp overnight before you even set up your tent!

6.2.3 Weather resistance

My Naturehike Cloud-Up 3 Upgrade has a waterproof rating of 4000mmHH (Hydrostatic head).

Hydrostatic head (HH) is the amount of water, fabric can resist before it leaks through, measured by the height of a column of water. So, my flysheet, or outer layer, could withstand a column of water 4m high before it leaks through. That’s pretty good, and reassuring, particularly considering British weather, and my declared three-season intent.

Can you believe I never even considered how waterproof my first tent was, never mind how one would go about measuring that, before purchase, despite it being, pretty much, the central purpose of a tent. All because it had nice windows!!!

Another factor to consider is your tent’s footprint, or ground mat. After spending so much on your tent, you don’t want to puncture the floor of it on your first night camping. So, you need to always make sure you clear the ground you plan on setting up your tent with your gloved hands to remove any sharp twigs or stones, or worse, glass or needles! And then use a footprint under your tent.

A footprint was included with my Naturehike Cloud-Up 3 Upgrade, because of the ‘Upgrade’, but if yours isn’t, you will need to purchase it separately, which obviously adds to the price of your shelter system.

The alternative is buying a separate ground sheet elsewhere, which isn’t as easy as you’d think. It needs to be the same size—just a little less—as the internal floor of your tent. Needless to say, practically impossible with my first dome tent, because mine was a hexagon. (It would be!)

And if your groundsheet is wider than the floor area of your tent, like a saucer below a cup of tea, it will serve the same purpose, and catch the overspill from your tent and collect the water under your ‘cup’, leading to a puddle underneath the floor of your tent, below your sleeping bag, which will inevitably slowly seep through.

Further, my next wild camper beginner’s big mistake with my first tent was to buy an aluminium camping ground mat, see photo above, because I thought that would add insulation, but although it weighed 200g which is good, its packed size—which they don’t state in the Amazon description—seemed larger than a child’s school bag(!) because it couldn’t fold so easily. (Another case where less is more!)

Invest in a decent footprint made by the manufacturer of your tent to protect, and prolong the life of, your tent, which will save you money in the long-term, by not having to buy another one so soon.

6.3 Sleeping system—What sleeping bag is best for wild camping?

6.3.1 The best sleeping bag for wild camping

This is the million-dollar question when you’re wild camping because you make your bed and you have to lie in it(!) The first consideration, again, is weight—it usually is—which is almost inversely related to the second consideration, which is warmth; the heaviest bag is more likely to be the warmest.

Except like any other wild camping gear, the more you pay, the lighter your sleeping bag will probably be for the same level of warmth.

When it comes to level of warmth, you can’t trust most budget manufacturers’ declarations. Forget how many seasons they say their sleeping bag is, or what temperatures they claim are ‘comfort’, ‘limit’ or ‘extreme’ unless they have been independently tested to an internationally recognised standard for thermal insulation, which for sleeping bags in Europe is called EN13537 (EN=European Norm), and in America, is called ASTM F1720-17 (American Society for Testing and Materials).

The EN13537 uses a thermal manikin test, like the one in the photo above, with temperature sensors dressed in base layer, socks and a warm hat placed in the sleeping bag being tested in a cold chamber, and the manikin measures the power needed to keep a constant skin temperature of around 34°C. The thermal resistance of the sleeping bag is measured in RSI which is converted into four temperature ratings in either Celsius or Fahrenheit degrees using formulas and historical data: Upper Limit, Comfort, Lower Limit and Extreme.

However, it is very difficult to find a budget manufacturer who quotes the international standard they have used to determine their temperature rating, which may be because it is costly to have this tested, which would presumably have to be fed back into the price.

I was also concerned about the width of the sleeping bags I researched, which were only 75cm in diameter, and I am quite broad, and would struggle to sleep in this. The most budget friendly three season, and wider, sleeping bag I could find was a Trail Cotton Flannel Sleeping Bag (300gsm) at Trail for £35.99 which measures L220cm x W85cm, weighs 2.24Kg and provides “optimal comfort at 0C to 10C.” However, it doesn’t state on their website whether this is independently tested, so I wrote to them.

Here is their reply:

This reply didn’t exactly fill me with confidence, but to be fair to them, at least they replied and I suspect many ‘budget’ sleeping bag manufacturers do not test according to international standards.

The cheapest budget three-season sleeping bag I could find with the EN13537 standard was the Vango Nitestar Alpha 300 Quad (which sounds a bit like a four-wheel vehicle!) which provided a comfort rating of 0C, Lower Limit -6C, Extreme Limit -23C, internal chest width of 78CM, packed size of 33cmx27cm), 2kg, but it was £44.95! And I didn’t want to spend much more than £36 plus postage.

But then I had a brainwave, what about a military sleeping bag?

The British Army FESCA sleeping system is officially designated as the U.K. Ministry of Defence Modular Combat Sleeping System and the medium weight bag’s Nato Stock Number (NSN) is 8465-99-858-2074. It comes in medium and large sizes, and the larger size measures 212cm (L) x 81cm (W), weighs 2.2kg, and is made of ripstop nylon with “Hi-Tec” insulation and a comfort rating of “-10 (approx.)”[14] .

I have outdone myself on beginner mistakes here, because it being a concurrent military piece of equipment, the Ministry of Defence are unlikely to disclose much information about it, including the Upper Limit, Comfort, Lower Limit and Extreme temperature ratings (Like flagging their position: We’re over here in the arctic! Joke!) Never mind whether it has been independently tested to the EN13537 standard!

However, it being military, I think it’s safe to assume it has been rigorously tested for thermal resistance by the Ministry of Defence (MOD) Defence Test & Evaluation (T&E), (if you have any complaints!) It is apparently made in Spain, though, by Fabrica Espagñola de Confecciones SA (FESCA) and remarkably similar(!) to the popular worldwide, and much more expensive, Carinthia Defence 4 £190.

The British Army FESCA sleeping bag is part of a system of three interlinking bags to cover all the seasons, therefore, you can add the liner and lighter weight summer bag inside if you need to go winter wild camping! And it is wide enough for me, because the British Army sleep with their weapons. Here is a very flattering YouTube Review.

This medium weight Army sleeping bag retails at around £100 new, which was way beyond my budget, but I managed to find one second-hand for £31.50, and you can find one similar here.

This is the only beginner’s mistake I didn’t make; when you haven’t been wild camping before, don’t buy anything new before you’ve even tried wild camping – you don’t know if you’re going to like it!

I thought you can’t go wrong buying second-hand if it’s not just “Grade 1,” but “Grade 1+”!

Everything looked great outside the sleeping bag, it even smelt washed and fresh, but when I turned it inside out, you can see the sad results of my purchase in the photo below (I hasten to add this sleeping bag was not from the supplier given in the price quote or supplier in the picture above, and shall remain nameless):

I know, I know, I know. Beginner mistake a million and one, I should have purchased the Vango Nitestar Alpha 300 Quad in the first place!

(Please learn from my mistakes to save yourself the pain!) The Vango even comes with its own compression sack.

The British Army FESCA sleeping bag does not come with a compression sack or bag, but there is no way I would have been stupid enough to purchase one second hand again (!) for £10.99 from the same place?

Yes, I did. And it was sandy, oily and dirty with names inscribed all over it and a broken buckle to boot! Let this be a reminder that you do take a risk when you buy army surplus gear and I had no hesitation in immediately returning it for a refund.

But I hesitated about returning the sleeping bag. The problem is the British Army FESCA sleeping bag was very warm and comfortable when I tried it out—it actually seemed to work—and just felt right. So right, however wrong it was, I didn’t want to lose it.

They offered me a full refund and return paid postage for both, or replacement of both, and on the basis that I could return the replacements if there was something wrong, I accepted their offer to replace them. I will update you after I have tested the sleeping bag in the field, assuming it arrives in a decent condition, which is the only way to test its thermal insulation.

However, the insulation standard of your sleeping bag is only half the story, when it comes to warmth. The other half is what your sleeping bag is lying on.

6.3.2 The best sleeping mat for wild camping

If you didn’t know, EN sleeping bag “comfort temperature” ratings assume you are using the bag with a sleeping mat with an R-4.0 value[15], so you might as well rule out all the EN rated temperatures anyway unless you have an R-4 sleeping mat!

In other words, if you are lying on the cold ground, it doesn’t matter what insulation standard your sleeping bag has, you will probably be cold without a ground mat.

That’s why a ground mat is essential, and like a sleeping bag, it needs to be independently tested to an internationally recognised standard, which is different for ground mats, and in Europe is EN12667 and in the US, ASTM F3340-22[16] (2022) or the slightly older, ASTM F3340-18 (2018), and an R-value is given, where R stands for Resistance, in this case Thermal Resistance. A higher R-value indicates better insulation and greater suitability for colder weather.

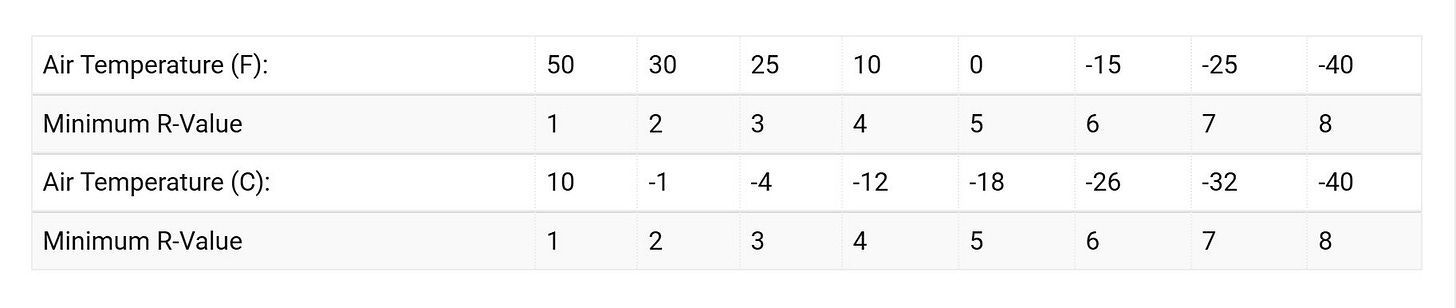

The table below shows how R-values compare to Air Temperatures, which can be accessed from weather reports and historical temperature data, for example, from the Weather Underground. NB. This SectionHiker estimated table is based on Exped recommendations[17] and R-value standard ASTM F3340-18.

There is also a useful comparison of different ground mats and their R-values, on SectionHiker here, albeit for mostly the top-end premium sleeping mats.

Women tend to sleep colder than men, and as a general rule of thumb, women should add +1 to the R-value they need.

There are four types of ground mat, and in order of approximate cost (2025), they are: closed-cell foam mats (£10 -£60); inflatable mats (£15-£150); self-inflating mats (£20-£180), and insulated inflatable mats (£50-£250).

Ground mats can start below £10 for a ‘blue-foam’ closed-cell EVA (Ethylene Vinyl Acetate) pad with foil backing from Amazon (£7.99) , which is very light (0.16Kg ) and an “estimated R-value of 1.4” [estimate seems a bit high imho!] making it suitable above 10 degrees Celsius, reading from the above table.

However, be aware that it is very narrow, at 50cm (180L x 50Wx 0.6Th) but this seemed to be true of most of the ground mats I researched, regardless of cost, even military ground mats.

And it is very thin at 0.6cm, which at my age, is a big ask! Don’t get me wrong, I have slept on my share of floors in my time so I don’t mean it in a snobby way, but ironically I suppose, I don’t want to suffer on my pilgrimage! So, I wanted a wider and thicker inflatable mattress that provided more comfort.

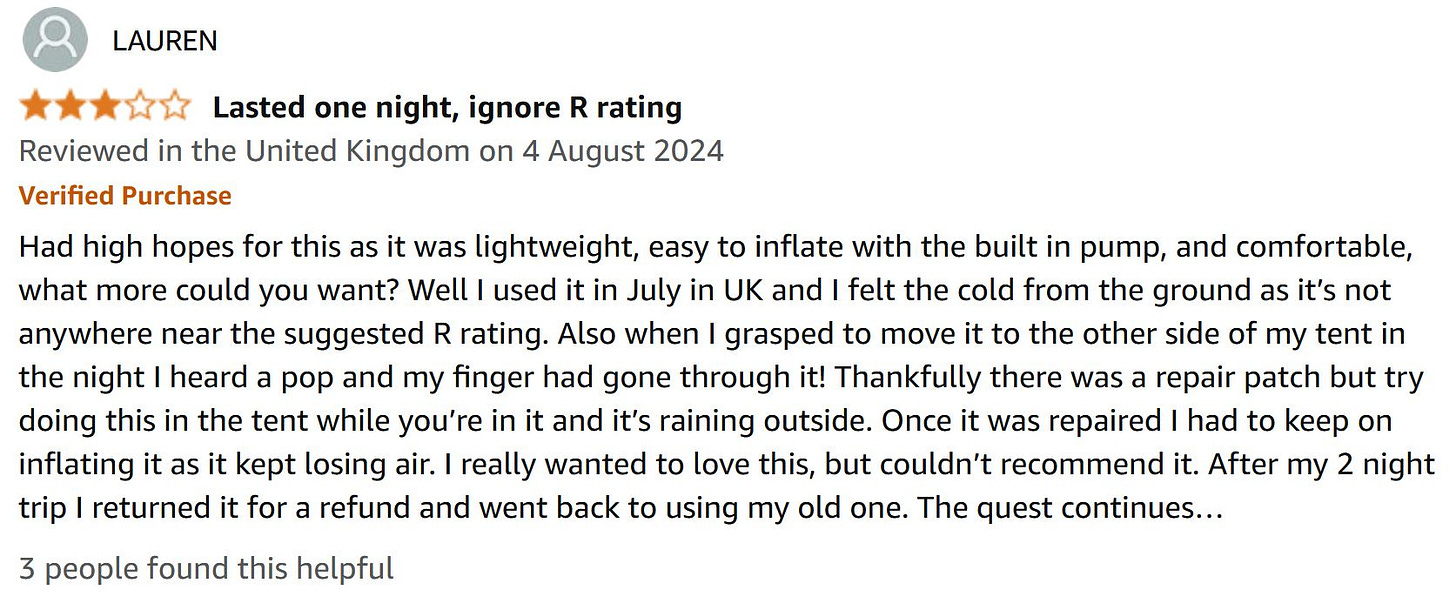

You can see the inflatable mattress I bought, £32.99 from Amazon here, in the photo below, and the key features for me were its light weight (1.02kg), wide width (72cm), deep depth (12cm) and inbuilt pump. But it also has a raised pillow, and ridges on the side which is a nice feature and, I thought, might help me from falling off!

However, being the wild camping beginner I am, I made beginner mistake number…I’m losing count!... which is considering comfort before warmth! I not only didn’t understand the importance of whatever the “R-value” meant, and so the seller’s claim that it had an “R-value of 3.5-5” didn’t mean anything to me, I didn’t think about which standard was used to measure this? EN12667 or ASTM F3340-18/22, so how did I know if it was accurate? (They didn’t mention either in the amazon description!)

However, if I’d read more than the first page of reviews: I would have seen Lauren’s review, “I used it in July in UK and I felt the cold from the ground as it’s not anywhere near the suggested R rating.”

Although it is worth remembering here the R-Value Addition Rule: R-values are cumulative, so if I used the cheap blue-foam mat mentioned earlier with an estimated R-value of 1.4 and this inflatable mattress, with an R-value of, just say, 2, on top, they would have a combined R-value of 3.4, which would allow you to camp more comfortably above -4°C. But this seemed a little like throwing good money after bad.

Following more research, I found the Robens Campground 50, which is more expensive, £49.99 from the Robens website here, but it has an R-Value of 4.1 (-12°C), width of 63cm which is still pretty good, length of 195cm, and a depth of 5cm, which is enough for me.

I emailed Robens to ask whether they had used the ASTM standard to calculate their R-value—once bitten twice shy! —and they replied with good news, see photo below:

The packing size for this ground mat is only 32cm x 20cm, and I checked my rucksack first this time, and yes, it can accommodate this easily. The only downside is that it is not a premium ultralight ground mat, and relatively heavy at 1.64Kg. However, alternatives are twice the price for half the weight, but you’d need two to achieve the same depth!

I still wasn’t sure that the R-value of 4.1 would be enough, though—maybe another beginner mistake not to try and see first(!)—and remembering the R-Value Addition Rule, above, I wanted to buy a Zigzag sleeping mat to go underneath.

Mod and Tara, my favourite UK nomads, swear by the Therm-A-Rest Z Lite as the only sleeping mat required in their Wild Camping for beginners video here—no inflatable mattress necessary for them— turning the foil side towards or away, depending on the winter or summer season, respectively.

This is a closed cell, polyethylene (PE) mat (£50 on Amazon), 51x183x2cm, 410g, foil-backed, with an R-value of 1.7 and, to be honest, the sleeping mat that everyone on all the forums recommends, but this was too narrow for me as a side sleeper at only 51cm wide, and, frankly, too expensive for me.

After a lot of research I found the Robens Zigzag Slumber Pro (£36.99 on Amazon), a similar looking but XPA closed-cell foil-backed foam mat, wider and thicker at 192x60x2.8cm, although 210mg heavier at 620mg, but with a higher R-value of 2.4, providing additional comfort and warmth which were my priorities.

On questions of gear, you always have to drill down to the purpose of your camping, your ability (fitness and strength), and comfort expectations. As long as I can stay within my target of 12-16kg, I am sure I will be fine. It may be worth adding here, that 16Kg is the maximum weight I can carry, not the pack base weight.

The base weight is the weight of all the equipment excluding consumables like drink and food, which can easily add another couple of kilos, so subtract this from your maximum weight before you start buying gear. Remember each 1 litre bottle of water, and you need to consume at least two a day depending on body size and gender, is an extra kilo. Unless you can refill along the way, you will need to carry what you need to consume daily.

In order to refill along the way, you need to think about how you will process recovered water, and what you will eat, which I will consider next in the cooking system.

6.4 Cooking System

6.4.1 How to filter water for wild camping

You can only survive three days without water, according to the wilderness rule of 3: “3 minutes without air (oxygen), 3 days without water, and 3 weeks without food”[18]. Although I think the latter is based on ‘if Gandhi can, anyone can!’[19]

I plan on a three-day pilgrimage, and three days of water, if I had to carry it, on the basis of 2 litres a day, would be six litres (6Kg), which is too much for me to carry in addition to my base weight. Therefore, I will need to collect recovered water and process it by either filtering or boiling water, or ideally both!

Portable water filters cannot filter out viruses[20] and must have, according to the CDC, “an absolute pore size of 1 micron or smaller to remove parasites (such as Giardia or Cryptosporidium)”[21]. This is important because one of the most popular portable filters on the market has a pore size of 2 microns, which shall remain nameless, this may give it a faster flow rate, but at what cost!

Boiling water for 1 minute (above 2,000m for 3 minutes) after filtering will kill most pathogens, including viruses, bacteria and parasites. Although, boiling water alone won’t filter out sediments or microplastics like the portable water filter will, so use the portable water filter first and then boil.

“Water filtration removes germs by physically blocking them while letting the water pass through the filter. Unfortunately, filtration will not remove all the germs that can make you unwell. You will also need to use chemicals or boil filtered water to make sure it is safe to drink.” – NHS Travel Advice

If you can’t boil the water, use a chemical disinfectant, like iodine, chlorine or chlorine dioxide, after the water filter, but this is not necessary after boiling, and could potentially affect the taste.

A useful tip to ensure the best tasting water and prolong the lifespan of your water filter is to use a pre-filter, like a coffee filter, to remove larger particles, sediment, and debris from recovered water first, which may otherwise clog up your portable water filter. This is supported by research on the effectiveness of coffee filters as a pre-filter for “removing PCR inhibitors, such as humic acid, in wetland habitats.” [22]

The best lightweight/ultralight water filter according to Outdoors Magic and Clever Hiker is Katadyn BeFree for £50 at Amazon. It weighs 59g with a flow rate of 2L/min, a 0.1micron pore size filter, ‘ez-clean’ membrane—easily cleaned by shaking or swivelling—lifespan of 1000L, and capacity of 600ml.

However, because I intend to boil any water I filter to remove viruses, I don’t want a handheld bottle, but rather a gravity water filter that I could hang up with a tube to a collection bottle (like my pan for boiling) and ‘leave running’.

Clever Hiker recommends the Platypus GravityWorks (like this one for £84 at Amazon), which weighs 268g, with a flow rate of 1.5L/min, a volume of 2L, but please note a filter pore size of 0.2 microns, which is why I prefer the Katyden Water Filter BeFree Gravity 3.0 Litre (£66.95 at Amazon), which has a filter pore size of 0.1 micron, is lighter at 100g, and has a larger capacity at 3L. It’s also cheaper!

After pre-filtering recovered water with a coffee filter, filtering with a gravity filter, and boiling the water you will have a safe and regular supply of water for all your daily needs, you just need to plan your hikes passed, and/or pitches, near a water source.

Now we need to consider the best way of boiling the water, because the Wild Camping Cardinal Rule, above, is to light no fires, and ideally a combination that works best to cook food, too.

6.4.2 How to cook food for wild camping

There is a wonderful YouTube video here exploring the evolution of Trevor’s culinary wild camping journey, including the Spirit stove, what he calls a ‘Trangia Stove’, because Trangia AB introduced their iconic spirit burner in 1951 (like this cheaper one for £10.99 at Amazon).

The good thing about a Spirit stove is it is relatively cheap, extremely light (0.14kg), so small it could fit in your pocket (9.7L x 9.7W x 6.5Hcm), high output (estimated 500-1000W although it claims 2600W, which must be an error). You can use bioethanol liquid fuel (1L is £7.49 on Amazon —rough guide 30ml for 40mins, according to one commentator) which is a relatively cheap fuel and arguably more environmentally friendly. And the spirit stove I have linked to, see photo above, includes a foldable handle flame regulator, stove base and carry bag. You will also need a Windshield (like this one for £5.99 on Amazon), and a pot (like this small set for £11.99 at Amazon) giving you the cheapest wild camping cooking system money can buy (that doesn’t involve gathering or burning wood) for under £40—Only £36.46—including two pots, knife, fork and spoon!

It doesn’t state the time it takes to boil water, but the traditional, and original, Trangia Spirit Burner (£14.99 here) takes 10 minutes to boil 1L of water, and 100ml will burn for approx. 25 minutes, depending on the weather and the quality of the fuel, which is good for boiling approximately 2 litres of water, which means you could potentially boil 10 litres of water with half a litre of fuel, enough for a 5-day trip.

However, the fastest and cheapest method of boiling water is to get a Jet-boil style APG 1.4L Camping Stove with integrated pot (£43.20 from Amazon) which weighs 427g, 120mmx120mmx240mm, 1400W maximum power and can boil 1L of water in an estimated 5-6 minutes, almost twice as fast as a spirit burner.

You will obviously also need a gas canister, ( individually £7 on Amazon or 6 x 230g for £22.99 on Amazon—approx. £4 each) giving you a wild camping fast cooking system for £47.20-£50-208. Another tip to save more money, you can buy a gas canister transfer valve (£7.99 from Amazon) to fill up smaller gas canisters from bigger gas canisters.

It was a very difficult decision to choose between the two cooking systems because even though the APG is obviously faster, speed isn’t an issue when you’re camping and have all the time in the world.

The APG is also heavier and bulkier than a spirit stove because of the gas canister.

The deciding factor for me was safety.

Although you should always cook away from your tent when wild camping to avoid the cooking smells identifying your tent’s location to a passerby, dog or wild animal, this is mitigated by cooking pouches in boiling water which I would like to do in the vestibule of my tent with the door open.

You can find wild camping meals in pouches requiring no refrigeration and just boiling water to re-heat from Wayfayrer, all day breakfast (£5.95); Firepot, Beef Stew (£5.50), Expedition Foods, Spaghetti Bolognese (£8.54 ), Adventure Food, Vegetable Hotpot (£6.50), Summit to Eat, Chicken Tikka with Rice (£8.99) or military ration packs. Or you can make your own using mylar pouches.

However, never cook with a gas canister stove inside your tent for any reason, including keeping warm, because of the danger of carbon monoxide poisoning, which is an odorless gas that can kill you.

But an open vestibule is relatively safe with a gas canister stove, especially if you are just boiling water, and it is very common in many wild camping YouTube videos.

On the other hand, spirit burners are inherently less stable, and the risks of spills and flare-ups is higher compared to a gas canister stove, especially in the confined space of a vestibule. And, in the end, this was the deciding factor, and why I chose the APG 1.4L Camping Stove.

But, in all honesty, and try not to laugh, that was not before I had initially splashed out on one of these:

Yes, the red (I must have a thing about red!) Green Haven Portable Gas Stove with Automatic Ignition & Heat Control (£16.99 from Amazon) because, well, it looked like a mini version of my stove at home! My excuse? The familiar is comforting.

But it is bulky and relatively huge at 36L x 9W x 31.5H centimetres, although it comes in its own sturdy carry case (that should have been a clue that it wasn’t designed for wild camping, if the colour wasn’t!)

On the plus side, it has a very reliable power output of 2100W, using butane gas cartridges, is EN417 compliant, but on the negative side, weighs a whopping 1.43Kg; more than double the weight of the APG 1.4L cooking stove with an integrated pot, including the gas canister, and without a pan!

It is perfect for car camping, ludicrous for wild camping. (At least I’m honest!) And I must say that during my wild camping cooking practice in my kitchen, it is remarkably easy to use and reliable.

Now, if you’ll excuse the expression, what goes in, must come out, and we can’t do a deep dive on wild camping here without considering the sensitive topic of toilets.

6.5 Toilet System - How do you go to the toilet when wild camping?

Toilets are what keep campsites in business because in wild camping there are none as we know it, although I found an ingenious solution.

But first, the normal procedure for urinating/defecating in the wild is to make sure you are at least 30m away from a water source and dig a hole with a trowel at least six inches deep to bury your human waste and take away any used toilet paper or wet wipes. I bought a Portable Folding Camping Shovel (£9.99 from Amazon) which is 46.5cm long, miraculously folding to 19cm, and weighs 710g, which is heavy but it can also be used as a hoe or saw (when you’re not wild camping, of course!)

You can get trowels which weigh next to nothing and achieve the same purpose like this Ultralight Aluminium Camping Trowel (£7.55 from Amazon) weighing 18g, see photo below, if I had for a single moment contemplated the ever-increasing weight a three-in-one spade would be adding, never mind a 46cm shovel being somewhat overkill for digging a little 6-inch hole!

Pro Wild Camping Toilet Tip: Tara from Log Hoppers – The official UK Nomads advises sticking a stick in the spot you use, so you, or other wild campers, don’t inadvertently dig it up again! And remember to take away, and not bury, your tissue or wet wipes.

However, squatting low to the ground to defecate, which is actually healthier for your body, requires balance and hardier wild campers than I have apparently taken Imodium, the diarrhoea treatment, to avoid defecating altogether while wild camping, which I don’t recommend. Others time their overnight journeys and go only when they have already defecated.

However, I found an ingenious solution, a truly collapsible and height adjustable portable toilet!

This portable camping toilet is not cheap (£54.26 from Amazon) but comes in heights/weights of either 33cm/1.2Kg or 50cm/2.7Kg, and for once I didn’t make the beginner mistake of choosing the most comfortable height, instead opting for the lightest. Although doubtful it would work, I am pleased to say, although tight, I am 182cm and 80Kg, it worked fine. I am willing to sacrifice 1.2kg for a private convenience.

Now we’ve considered navigating to the loo, it’s time to consider navigating to the best location for wild camping.

6.6 Navigation System - where to go wild camping?

I started by looking for inspiration for the most suitable pilgrimage in terms of my fitness for hiking and wild camping ability-beginner on the British Pilgrimage Trust website.

I chose Wells Cathedral as my target, see photo below, which has, according to its website, been “inspiring pilgrimages for nearly 850 years” and the 20-mile route (7.5 hrs) there from the coast at Weston-super-mare (2hr 30mins from London on the train) along the West Mendip Way, makes a scenic round trip back to Weston-super-mare train station of approx. 40 miles (15hrs) total.

I figured this was feasible with an overnight stop after 8-10 miles on the way there and one on the way back. A two-night three-day wild camping trip.

The next thing I did was buy two Ordnance Survey Maps, 1:25000 scale, which covered the route: Weston-super-mare & Bleadon Hill (No.153) (£4.99 from Amazon) and Cheddar Gorge & Mendip Hills West (No.141) (£8.99 from Amazon). These also included free downloadable maps to my phone using the OS app.

I suppose you could just use Google maps but OS Maps clearly show you trails and public footpaths as well as indicating types of land and elevations, which is useful when determining where to pitch your tent.

I also bought a Highlander waterproof map case (£13.99 from Amazon) 30cm x 27.5 and weighing 0.16Kg.

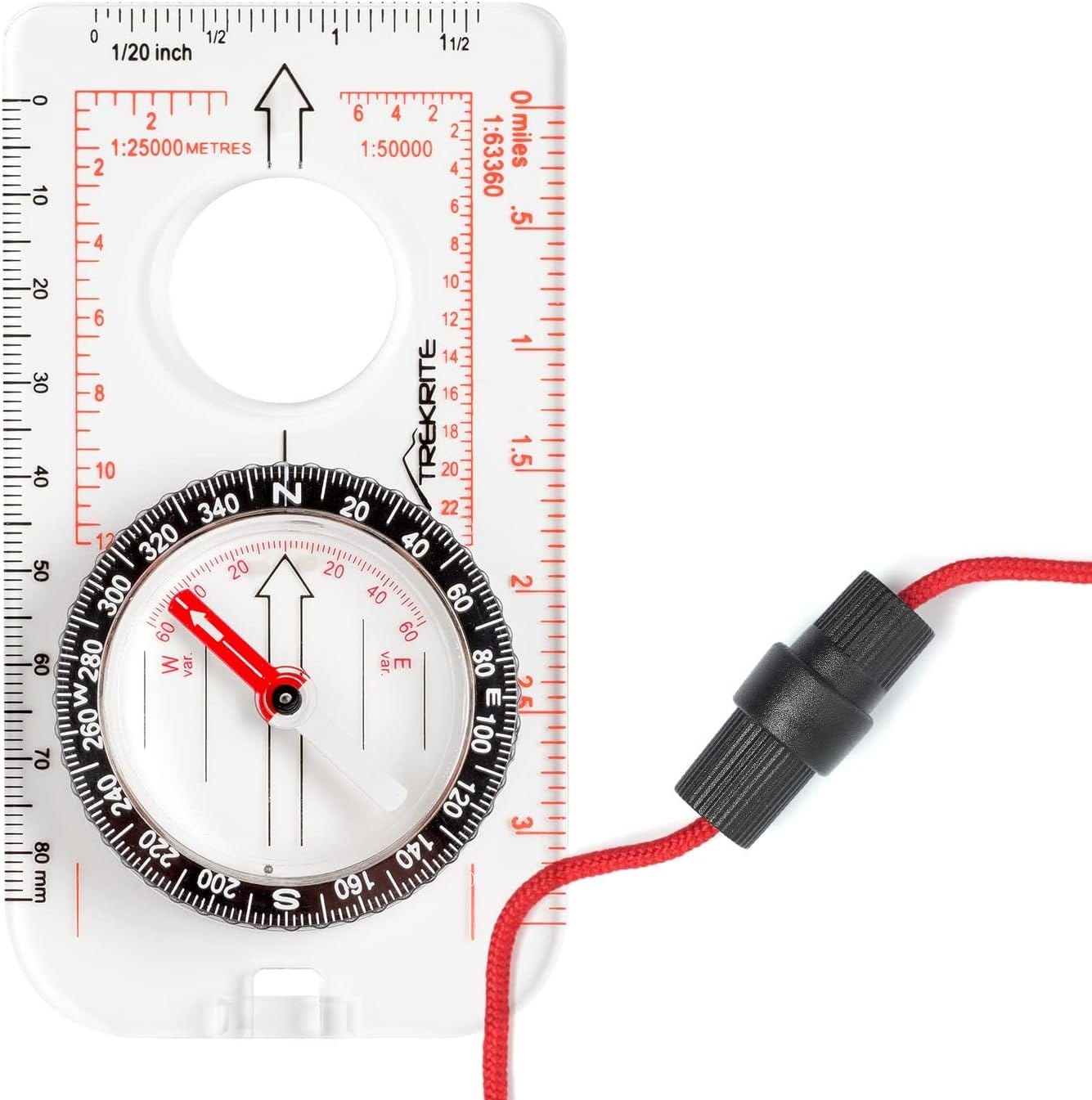

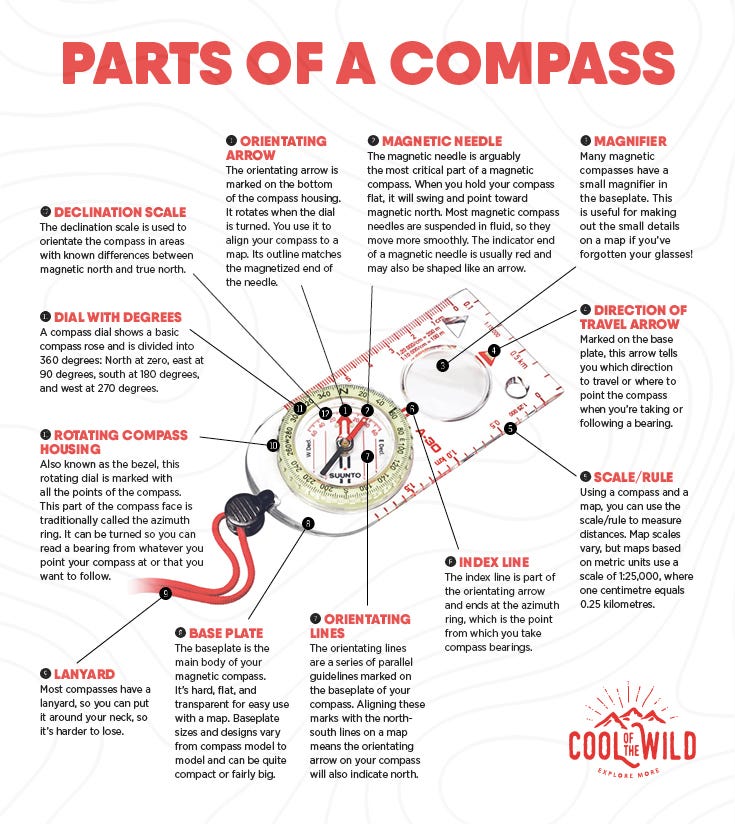

And I bought the cheapest good-looking compass I could find because I thought a compass is just a compass, right? Wrong. Big Beginner mistake!

Your compass needs to have a clear index line, see infographic below for a description of all the parts, which my first compass, incidentally, otherwise looking exactly like the one in the infographic, failed to have. And the clearer the index line the better.

The most popular brand of compasses is Silva Compasses, but they are expensive and the second compass I selected was a Trekrite Explorer Compass (£9.99 from Amazon), see photo below, which includes a clear index line and sixty degree declinations East and West, which was good enough for me. It is important to adjust your heading from maps according to magnetic declinations because these can change over time.

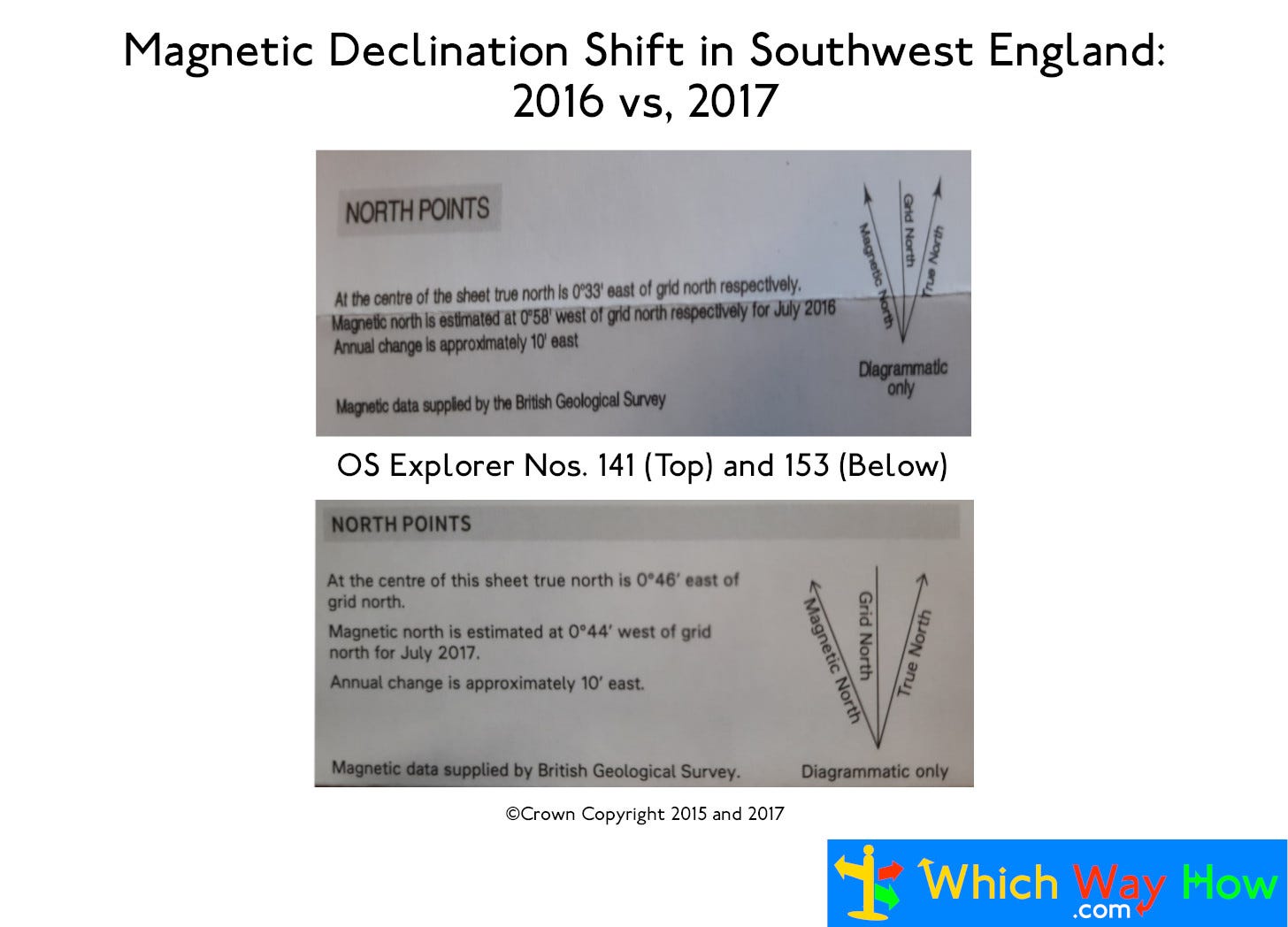

When I was examining my two maps, mentioned above, I noticed a difference in True North, which is to be expected because they are neighbouring maps in Southwest England, but also in their Magnetic North: 0°58’ west of grid north in 2016 vs 0°44’ west of grid north in 2017.

The reason for this is magnetic declination is always shifting and these readings were taken a year apart, see photo below.

Therefore, it is important to find the most current magnetic declination, which, for example, in Weston super mare in 2025, where I plan to start my pilgrimage, is about 0°34’ East, compared to 0°44’ West in 2017, which is over one degree from True North different, see photo above.

Remember that declinations for Magnetic North change over time, with the flow of molten metal in the earth’s core, so if you use an old map, the declination given may be wrong. You can find the current magnetic declination for your location at the British Geological Survey or the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration if you know your current latitude and longitude.

The easiest way to find your latitude and longitude is on google maps by placing a marker with a finger-tap on any spot, the latitude and longitude will appear above.

Remember that latitude refers to how far North or South you are of the Equator, like on the Y axis, and longitude refers to how far East or West you are of the Prime Meridian, which runs through Greenwich, London, like on the X axis. But it is odd that we always write Latitude followed by Longitude, in grid references, including Google Maps (Y, X) rather than like mathematical coordinates (X,Y) but that is the tradition!

If you’re new to map reading, there is an OS Guide to map reading here.

You can also use Compass app, on your mobile phone, instead of a physical compass. This will automatically point to Magnetic North, like a physical compass, but you should remember that it is not pointing to a particular place, but rather aligning with the parallel magnetic lines of the Earth’s magnetic field. You adjust for magnetic declination when you are using a map, because the grid lines all follow True North.

If you rely on your phone for navigation, though, rather than a physical compass, remember to bring a power bank/phone charger.

I invested in a rugged waterproof solar power bank similar to the one in the photo below (£36.88 from Amazon) but mine was 46,800mAh, or so it claimed.

To my horror, after charging my power bank fully, and then my phone, I calculated—using a long and convoluted process I shan’t bore you with here—that it had a capacity of only 30,000 mAh!

This meant I could only charge my 4,000 mAh phone battery 6 times, although this was still enough for a 2-night pilgrimage. It was also waterproof so I could leave it outside my rucksack if it was sunny to be charged by the solar panel while I hiked. The downside is it weighs 600g.

Although it contains a flashlight, which is useful when looking for a pitch if it gets dark and/or inspecting the ground, it is hard, if not impossible, to read your map in the dark, at the same time as holding a powerbank /torch.

Therefore, you need a head lamp, which is also useful for keeping your hands free for cooking in the dark or going to the toilet.

I got a headlamp like the one below (2 for £14.99 from Amazon) which is waterproof IP65, only weighs 50g, 2000 Lumens bright, and has a 2000mAh rechargeable battery with micro USB, which I can recharge from my power bank!

It is also hands-free, in other words you can turn it on/off with the wave of your hand, and you can tilt it down, and I found it then followed directly where I was looking. (And having two is useful because you don’t want to have wait for it to recharge if it suddenly runs out of charge, and you, say, urgently need the toilet!)

Finally, if you do get lost and find yourself stuck or injured in an emergency situation, you should always carry an emergency whistle. I bought one like this (£3.09 for two from Amazon), 55cm x 10cm, and you can hang it on your keys and forget about it.

You can use your whistle to communicate in Morse Code, but The Emergency Whistling Protocol, or international distress signal, if you need emergency help is to blow six times every minute. And the acknowledgment by a rescuer will be three whistle blasts every minute.

However, it may be better not to give the acknowledgment until you have located the person in distress, or have them in clear line of sight, because, obviously, they may stop blowing their whistle for help if you do, and you may then have difficulty finding them!

7. Conclusion

It’s funny how what you can get on your back for wild camping can be divided up into no less than six subsystems(!) but you can see the importance of considering all in this guide—and I’ve tried to be as brief as possible, and it still turned into over 10,000 words!

When you start a new hobby there is always a steep learning curve. “Every change creates a need for learning”, as J Flower wrote, and “This change-induced learning has four phases: (1) Unconscious incompetence, (2) conscious incompetence, (3) conscious competence, and (4) unconscious competence.” [23]

I moved from the unconscious incompetent, not really knowing why a bright cream 5.5Kg tent might be unsuitable for wild camping when I bought it, to a conscious incompetent, I knew what I didn’t know. Now I am conscious competent, because I have thought hard and researched my buying decisions, and maybe one day I will be unconscious competent, and do it all naturally, without having to think about it.

I learnt the hard, and painful-on-my-wallet, way—which hurts even more if you are on a budget— using the heuristic(!) method (read: no method at all!) but hopefully you can learn from this old-timer’s many beginner mistakes, and make the right decisions first time, saving you time and money.

You’re never too old to start a new hobby and I sincerely hope you have a wonderful time wild camping and good luck on your first adventure!

Thank you for reading.

Someone asked me if they could buy me a coffee because I don’t offer a paid subscription, and if you would like to, too, here is the link.

If you enjoyed this post, please take a moment to like and share this post with others to help grow my newsletter—it really makes a difference—and hopefully benefits others, too.

To join the Whichwayhow problem-solving community and not miss out on my next FREE fortnightly investigative post to brighten your day— and potentially solve your problem—subscribe for FREE below now!!!

And if you’ve got any wild camping tips I’d love to read them in the comments below.

Happy Wild Camping!

References

[1] Sheldrake, R. (2017) Science and Spiritual Practices. Coronet. An Imprint of Hodder & Stoughton

[2] https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/wild-camping Accessed at 09.02 on 19th March 2025

[3] https://www.campingandcaravanningclub.co.uk/advice/camping-tips/wild-camping/ Accessed at 09.04 on 19th March 2025

[4] https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Geo6/12-13-14/97 Accessed at 09.09 on 19th March 2025

[5] https://www.dartmoor.gov.uk/about-us/about-us-maps/camping-map?SQ_VARIATION_78353=0 Accessed at 09.19 on 19th March 2025

[6] https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/dartmoor-camping-ban-court-of-appeal-b2377223.html Accessed at 09.13 on 19th March 2025

[7] https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/visit/lake-district/wild-camping-in-the-lake-district Accessed at 08.27 on 21st March 2025.

[8] Neale, S. (2015) Wild Camping. Bloomsbury.

[9] Neale, S. (2015) Wild Camping. Bloomsbury.

[10] https://www.fs.usda.gov/detailfull/fishlake/recreation/?cid=stelprdb5121831 Accessed at 09.52 on 19th March 2025

[11] https://www.hipcamp.com/journal/camping/how-to-find-free-camping-in-the-us Accessed at 10:12 on 19th March 2025

[12] Neale, S. (2015) Wild Camping. Bloomsbury.

[13] Clark, Gregory and Cummins, Neil (2014) Surnames and social mobility in England, 1170–2012.

Human Nature, 25 (4). pp. 517-537. ISSN 1045-6767 https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/60593/1/__lse.ac.uk_storage_LIBRARY_Secondary_libfile_shared_repository_Content_Cummins,%20N_Surnames_Cummins_Surnames_2015.pdf

[14] https://www.militarykit.com/products/british-army-sleeping-bag-midweight-olive-green?variant=55092155220341 Accessed at 13.02 on 23rd March 2025

[15] https://www.outsideonline.com/2371291/nerdiest-most-important-sleeping-pad-news-ever Accessed at 07.41 on 23rd March 2025.

[16] ASTM F3340-22. Standard Test Method for Thermal Resistance of Camping Mattresses Using a Guarded Hot Plate Apparatushttps://store.astm.org/f3340-22.html Accessed at 07.45 on 23rd March 2025.

[17] https://www.expedusa.com/pages/r-value-temperature-rating-guide Accessed at 08.49 on 23rd March 2025.

[18] https://svalbardi.com/blogs/water/living-without Accessed at 09.40 on 24th March 2025

[19] https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-long-can-a-person-survive-without-food/ Accessed at 09.43 on 24th March 2025

[20] https://www.thegreatoutdoorsmag.com/gear-guides/best-backpacking-water-filters/ Accessed at 10.12 on 24th March 2025.

[21] https://www.cdc.gov/water-emergency/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/emergency/making-water-safe.html Accessed at 10.31 on 24th March 2025.

[22] Takasaki K, Aihara H, Imanaka T, Matsudaira T, Tsukahara K, Usui A, Osaki S, Doi H. Water pre-filtration methods to improve environmental DNA detection by real-time PCR and metabarcoding. PLoS One. 2021 May 7;16(5):e0250162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250162. Erratum in: PLoS One. 2021 Sep 27;16(9):e0258073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258073. PMID: 33961651; PMCID: PMC8104373.

[23] Flower J. In the mush. Physician Exec. 1999 Jan-Feb;25(1):64-6. PMID: 10387273.